Coral Reefs: The Rainforests of the Sea

Kimberley McCosker

Coral – what marine biologists’ dreams are made of. Coral reefs are the reason many of us fell in love with the ocean – jewelled arms reaching towards the surface of warm, sunlight-dappled seas, tropical fish scattered throughout… Often referred to as ‘rainforests of the sea’, the colourful ecosystems are renowned for their diversity and their ability to safeguard an incredible variety of marine species.

For the month of June, we are taking a deep dive into the fascinating work of coral reefs, starting with corals in the cold, deep waters of areas like the United Kingdom and Canada, before looking at three of the biggest reef ecosystems in the world: the Coral Triangle, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, and the reefs of the Red Sea. Each week, we’ll share more information on the unique biology and tolerances of the corals that allows them to survive in such diverse locations, as well as up-to-date research being conducted in each region. If you want to learn more about the coral reef ecosystems we all love, keep an eye on our Facebook, Instagram and Twitter accounts throughout June, and keep an eye on #TMDdoesCoral!

The corals we are most familiar with are shallow water reef-building corals, which are comprised of a calcium carbonate skeleton and have a symbiotic relationship with a tiny, colourful algae called zooxanthellae. However, there are countless varieties of corals – reef-building hydroids, commonly known as fire coral (not a true coral); soft corals including sea fans and sea whips; and corals that exist without relying on zooxanthellae for food and energy, such as black corals and some cold water corals.

Corals form the infrastructure of intricate reef ecosystems that provide habitat, feeding, spawning and nursery grounds for countless marine species. However coral reefs are at the forefront of the fight against climate change, with many coming under extreme threat as a result ocean warming, acidification and other human-drive activities. Without coral reefs, many of the ocean’s most fascinating creatures would not survive.

Cold water corals

When most people think about corals, they imagine warm water, shallow reefs, bright colours and tropical climates. Yet these remarkable animals also flourish in cold, dark and deep waters around the world. Like their tropical counterparts, deep-water corals belong to the phylum Cnidaria – but while they have the stinging cells typical of this phylum, they don’t rely on the symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae to survive as the photosynthetic process cannot take place in the darkness of deep waters. Instead, cold water corals feeding solely by capturing food particles from the surrounding water. These corals are found all over the world – including the territorials seas of Canada, the United Kingdom, Norway, New Zealand, the Seychelles and Australia – usually in deep water along continental shelves, at the bottom of fjords and near hydrothermal vents or seamounts. Most live between depths of 200m to 1000m (660 feet to 3,300 feet) and they can thrive in temperatures between minus 1.8 and 13 degrees Celsius (29 – 55 degrees Fahrenheit) – a huge difference from the shallow, warm waters of their tropical cousins.

A Paragorgia sp. deep sea coral with polyps extended, while providing habitat for an orange anemone. Photo: NOAA OKEANOS Explorer Program, 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition.

Cold water corals are thought to be unique biodiversity hotspots in the deep sea, however due to their remoteness and the cost of required research equipment, existing knowledge on these reefs - including their ecological tipping points - remains limited. However, research is underway to improve the understanding and sustainable management of cold water corals. Preliminary finding show that, despite their remoteness, these corals are not averse to human impacts, with destructive fishing practices causing the highest impacts. Bottom trawling – the act of dragging enormous, weighted nets across the seafloor – devastates sensitive bottom habitats. Entire cold water coral habitats can occur, resulting in decreased abundance and biodiversity of the species that rely on these ecosystems for their own survival. With an incredibly slow growth rate of only 5mm – 25mm per year, it is critical to protect these ecosystems as regeneration will be a time-intensive process. Many cold water corals are beyond national jurisdictions due to their remote location, however conservation management measures are being developed through the United Nations and related international frameworks.

The Coral Triangle

Abundant coral reefs found in Raja Ampat, Indonesia. Photo: Madeline St Clair Baker.

If coral reefs are the rainforest of the sea, the Coral Triangle is the Amazon. The Triangle covers around 6 million square kilometres of ocean spanning from central Indonesia in the west, to the Solomon Islands in the east, and north to the Philippines – also including waters off Malaysia, Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea. The Coral Triangle is the global epicentre of marine biodiversity, and is home to the highest level of coral diversity in the world. Over 76 per cent of the world’s coral species thrive there, including fifteen species that are endemic to the region - meaning they are found nowhere else in the world. The diversity of coral species creates a fascinating study of the different tolerances of coral species: some of the healthier reefs in the region are found in dark, muddy, sediment-rich water; some species have adapted to living in greater depths and in cooler waters; others still have shown remarkable resilience to heat stressors, indicating potential to adapt to climate change.

Acropora coral is one of the more resilient coral species found in the Coral Triangle. Photo: Kimberley McCosker.

With the livelihoods of more than 120 million people and partial economies of six nations reliant on the Coral Triangle, the ecosystem is also a critically important resource. Because of the unique way in which humans interact with the eco-region, the Coral Triangle has been a hub for research with a focus on protection of the incredible reef ecosystems. Studies of coral fossils in the region have identified how ancient coral communities were able to tolerate low light, high turbidity, extreme temperatures and other marginal conditions, which is important to understand how modern reefs could potentially respond to the impacts of climate change. At the modern end of the spectrum, a start-up in the Philippines is using boat-towed cameras and sonar to create 3D underwater maps which are used by artificial intelligence systems to identify and monitor change over time - a significant advance in reef health surveying and monitoring methods which has led to the creation of new Marine Protected Areas.

The Great Barrier Reef

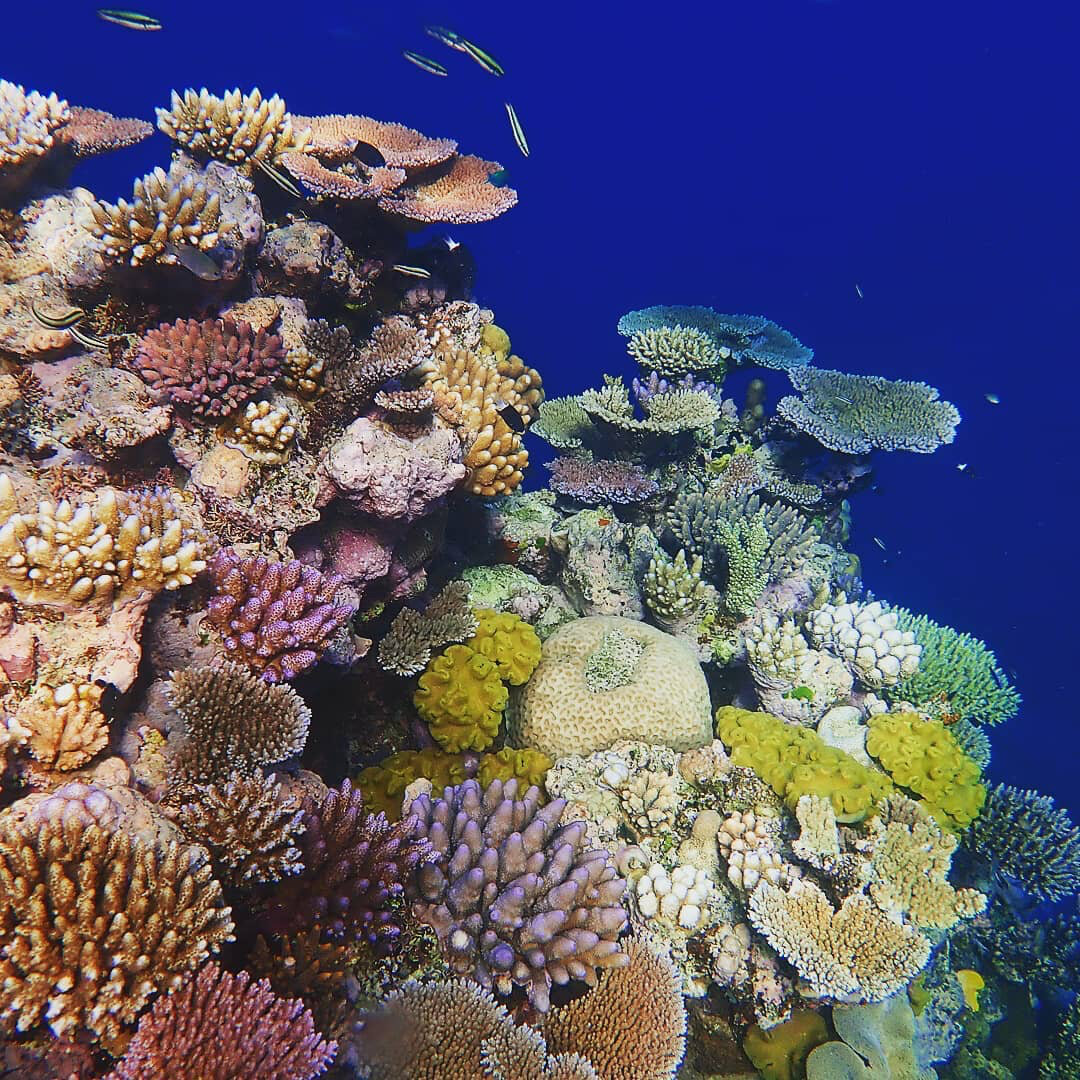

Vibrant corals off the coast of Port Douglas on the Great Barrier Reef. Photo: Kimberley McCosker.

There are not enough superlatives to describe the enormous beauty and ecological value of the Great Barrier Reef. The sprawling ecosystem is the world’s largest coral reef, composed over nearly 3,000 individual reefs and some 900 islands stretched some 2,300km down Australia’s north-east coast. The collection of reefs are home to 400 different species of coral and 1,500 species of fish as well as countless other marine species – giving it a globally unique array of ecological communities, habitats and species that warrant UNESCO World Heritage Status.

As well as its astounding diversity, the Great Barrier Reef is equally as famous as a clear demonstration of the disastrous impacts human activity can have on the delicate ecosystems. Human-driven climate change has led to abnormally high sea surface temperatures which triggers a stress response in zooxanthellae. When stressed, the algae abandons their coral structures, leaving only the white skeleton behind. The Great Barrier Reef experienced its third mass bleaching event in early 2020. This was the most widespread bleaching ever recorded, with over 60% of reefs affected along the entire 2,300km length of the Great Barrier Reef. After surveying the reef following this bleaching even, Australia’s leading coral reef researchers conclude the situation quite aptly: “What we saw was an utter tragedy”.

As well as this disastrous bleaching event, the Great Barrier Reef comes under constant threat from increased eutrophication due to runoff of farming fertiliser from the agricultural land that follows the reef along Queensland’s coastline, pollution from heavy metals found in pesticides, chemical-laden discharge from enormous mines, declining fish populations and habitat destruction from commercial fishing methods, extensive damage from shipping, and ongoing shark culling.

However, it’s thankfully not all doom and gloom. Recent research has shown the increasing tolerance of coralline alga to ocean acidification over multiple generations of exposure, while other scientists have discovered improved coral reef restoration techniques which may influence large-scale reef repair around the world. There are also moves to apply resilience concepts to coral reefs for integration into short- and long-term management and policy agendas, to help ensure the Great Barrier Reef is around for many future generations to adore.

The Red Sea

Vibrant coral in the Red Sea. Photo: Mae Dorricott.

Finally, we make it to the Red Sea. This unique body of water is an inlet of the Indian Ocean located between Asia and Africa. The tiny strip of water – just over 300km (190 miles) wide and 1,900km (1,200 miles) long - and hosts some of the most productive and diverse coral reef ecosystems.

While the Red Sea is heavily influenced by its booming coastal population, particularly the maritime transportation through the Suez Canal, as well as overfishing and largely unregulated tourism, it has shown remarkable resilience to the biggest human-driven threat of all: climate change. Recent research has also identified that corals in the Gulf of Aqaba, the northern-most portion of the Red Sea, are capable of withstanding temperature irregularities that cause severe bleaching or mortality in most hard corals in other areas of the world. Experiments conducted in the Red Sea Simulator aquarium system in Eilat, Israel, has tested about 20 different species of Red Sea corals found in the Gulf of Aqaba. These experiments have found that these corals can easily withstand temperature changes as much as 4-5 degrees Celsius above the current summer maximum, with some surviving as high as 7 degrees Celsius. Many corals also showed signs of increased health in these warmer waters, with their symbiotic algae doubling the amount of oxygen produced. Watch the video below to learn more about these fascinating experiments.

Researchers working on this long-term project believe these corals could serve as a model for restoration which climate change impacts and other environmental stressors are mitigated. With rapid ocean warming due to climate change predicted to decimate up to 90 per cent of the world’s coral reefs by 2050, findings like this are of critical importance to ensuring coral reefs survive and flourish long into the future.